- Home

- Iain Rob Wright

G is for Genome (A-Z of Horror Book 7) Page 2

G is for Genome (A-Z of Horror Book 7) Read online

Page 2

Adolf was a pleasant man, nearing thirty years of age. He was an avid painter and adorned the entire facility with bright watercolours and scenes of garish beauty. His talent was unremarkable, if admirable, and the act of creating seemed to bring the man a great and endless pleasure. A smile rarely left Adolf’s clean-shaven face. He was also always happy to sit and chat with Lester and today was no exception as they sat in his office sipping tea.

Lester’s reservations about what was being done here still lingered in his mind, but there was no denying the unique opportunity being presented. No psychiatrist in history had ever been given such an opportunity to explore the weight of genetics on a man’s destiny. The findings were already remarkable. Hitler was a prime example.

Allowed to focus on his artistic passion, Adolf was a compassionate and jovial young man, not the hate-fuelled monster who had waged World War 2.

“How are you feeling today, Adolf?” Lester asked from his side of the walnut desk.

“Very well, thank you.” Adolf spoke in the same plain English accent that all the guests did. It had been decided not to teach each guest their native language, as it would unduly complicate things. As a result, William Shakespeare and Adolf Hitler both spoke in the exact same dialect. It was disconcerting at first, until one understood that they were not the men from history, but brothers of a strange fashion.

Lester sipped his tea and then set the mug down on a coaster. “Is there anything you would like to talk about, Adolf?”

“Many things, yet I fear the answers would not be forthcoming.”

“You want to know more about the outside world?” Adolf often asked about current events. The man was inquisitive and yearned to know all he could about everything.

Hitler’s clone chuckled. “Wouldn’t you, Doctor? I know there is more to life than this building, and the trees and streams outside. The books I read describe a great many things that I fear I will never see.”

Lester swallowed. Stacker had explained that they tried to provide the guests only the briefest exposure to the outside world. Day trips were rare and meticulously organised so that the chosen guest never had chance to move beyond their joyous bewilderment of being out. The less they knew about the modern world the better, it had been decided. Yet, Lester thought to himself, the nature of man was to explore, and now at ages varying between twenty-seven and thirty-two, many of the guests yearned to break free of their modest existence. Adolf was the most eager of all to leave, despite his sunny disposition.

“I wish I could tell you what you want to know, Adolf. Perhaps one day all will be explained. I would very much like to be the one to explain it to you, but that is not my decision.”

“You would let me leave?”

“Perhaps.”

For a moment, Adolf’s constant smile slipped into something approaching a frown. “Stacker will never let me leave. He took me to town once. We sat and drank coffee at a little bakery on a delightful spring afternoon. The owner had a daughter who spoke English and she was most friendly. When I went to make use of the toilet, I bumped into this young girl and started a conversation.” He stopped for a moment, seeming to remember the moment fondly, but then his expression saddened. “She asked me where I was from, Dr Solberg. What on earth was I to say? That I lived in a warehouse with a family of some thirty-odd? No, of course not. I could only stare at her in confusion. Still she persisted in her interest of me. She requested my telephone number, to which I replied I had none. She laughed at me and I got upset. When I raised my voice, Dr Stacker came at once and grabbed me. I have not been outside this facility since. The consequence of me daring to have human interaction.”

Lester nodded. He knew the story. Slovakia was an ideal place for the facility because few of the natives spoke English, yet in recent years many of the younger generation had worked abroad and learned to speak it quite well. It made visits into town much more complicated now that the locals were able to question their strange English visitors. Now, only the most obedient guests were allowed on daytrips. Adolf Hitler was too headstrong to be among them. His inquisitive nose would lead him astray in the same way as a bloodhound’s.

“You are happy, though, yes?” Lester asked, not wanting his patient to dwell.

“I am healthy and alive. Many have less, I am sure.”

“You are correct, Adolf. The world is not so great a place. Your place here is unique, but not altogether unenviable.”

“Men envy power and I have none. My position is not enviable.”

Lester said nothing. He found it interesting when Adolf spoke. The man thought about concepts rather than details. Perhaps it was a part of his artistic nature that he often saw the big picture first and allowed the details to trickle in afterwards.

“You and Norma have been getting on well recently,” Lester commented, having noticed that Marilyn Monroe and Adolf Hitler were the greatest of friends.

Adolf actually blushed, fidgeted in his seat and fought a smile that sought to betray him. “Yes,” was the only reply he uttered.

“Do you care about Norma?”

“I care about all of my family.”

“Do you care about her in a way different to how you feel about others?”

Adolf shifted awkwardly in his chair. “Of course I do. No man and woman are the same, and neither are a man’s feelings towards separate individuals. I admit, however, that Norma is quite to my liking. Her spirit lifts me to soaring until I can think of nothing else but her smiling lips.”

“That’s quite beautiful, Adolf. Feeling that way is good.”

“Is it? I would like to think so, but a shared existence is not enough for a man and a woman to endure as one. I think I will pursue our friendship no further.”

Lester nodded sombrely, secretly glad to hear it. A relationship between guests could become messy and, as such, was not encouraged. “A shame. Anyway, I have detained you too long, Adolf, and I fear I lower your spirits when we talk.”

Adolf stood up briskly and offered a handshake. There was a warm, genuine smile on his face. “Not you, doctor; just the nature of things. I try not to think too much, but when forced to do so I find that my happiness eludes me in lieu of deep consideration.”

Lester frowned, wishing he understood the comment more, but knowing he had more guests to interview and a schedule to keep. “Take care, Adolf. We will speak again soon.”

“A pleasure I look forward to.”

***

Lester was still in his office come nine o’ clock, but the lights were dimmed and he sat alone with a bottle of brandy and a glass. He wasn’t expecting company when Dr Stacker walked in, but he found himself glad of it all the same. His mind was low and while he instinctively sought solitude, it also gave him little solace from his thoughts. Maudlin was how he would have described himself.

“All okay, Lester?”

Lester leaned forward and straightened himself. “Yes, all is well. I’m afraid I have only one glass.”

Stacker waved a hand. “I’m not a drinker anyway. I find it hard enough to get my thoughts in order without clouding them.”

Lester sniffed. “Sometimes it takes a little cloudiness to bring clarity. What can I do for you?”

“It’s been a few weeks now. I was just wondering how you were settling in. Wonderfully, from what I can see.”

“You have made my arrival very pleasant and the work is fascinating.”

Stacker leant forward. “But…?”

“But I still feel that this is unethical. I’ve allowed myself to be enticed by the wonder of the science at play here, but I still feel like a…”

Stacker laughed. “A criminal?”

“I was going to say monster.”

There was silence for a few moments until Stacker said, “Speaking of monsters, how was your interview with Adolf this morning?”

“Adolf is part of the reason I am feeling so very conflicted. He is a spirited soul. I feel like we are caging him here.”

<

br /> “We are,” Stacker said abruptly. “Can you imagine what would happen if we let Hitler’s clone out into the world? To us, and to him. It is the reality of science, Lester, that we must do what others will not. We are doing this for the betterment of our species.”

Lester rolled his glass in his hand, staring down at the sloshing, amber liquid. “To what end? What do we hope to accomplish here?”

“Many things. Can you honestly say that you have made no deductions from your short stay here? What are your thoughts on genetic destiny now that you have observed our guests?”

“I believe that our genes give us a framework, but what we do within that framework is very much up to circumstance. Adolf is a passionate and feeling man. I believe that is his genetic destiny – passion, perhaps obsession. The original Adolf turned that passion to things that were important to him at the time – misguided though they were. Our own Adolf is no different. Painting is his passion and that is where his focus currently resides. But I worry that the focus of his passion may one day change.”

“To what?” Stacker enquired, tilting his head curiously.

“To escaping. Adolf Hitler felt his country was unjustly treated by post-war Europe and he became a hate-fuelled monster as a consequence. I think our own Adolf is beginning to feel that he and the others are being unjustly treated. If there truly is such a thing as genetic destiny, then his may be war against circumstance. Defiance.”

Stacker was chuckling to himself now. “I must admit I thought your findings would be very different, Lester. Every doctor here has always found Adolf to be extremely affable. He’s a happy man, free to paint to his heart’s content. His ego is not stifled or restricted here. He has no reason to lash out. He is definitive proof that a man’s environment is more responsible for who he becomes than his genes. Adolf Hitler was not born evil, he was made to be.”

Lester refilled his glass from the bottle of brandy and took a large swig. “Perhaps. I am an old man and it is late. An old, tired mind is prone to wandering the fearful pathways of insecurity. I will continue to observe Adolf and the other guests and continue my findings. It is most interesting, I will admit that much.”

Stacker grinned. “We will change the world before we die, Dr Solberg, I promise you that.”

Lester took another swig of brandy and sighed. “For the better? Or for the worse?

***

Another two weeks and Lester had started to feel completely at home. He looked forward to waking up each morning, having breakfast with his colleagues and then heading into the common area where he spent his days conversing with Marie Curie, Edgar Allan Poe, and, of course, Adolf Hitler.

Hitler had been true to his word about not entertaining a romantic relationship with Norma, despite her obvious interest. She orbited his vicinity constantly and had taken up painting to impress him. Her skill with a brush produced nothing more than multi-coloured atrocities, but Adolf seemed to tolerate her company happily, if warily.

Speaking of paintings, Lester had noticed that Adolf’s style had evolved. Instead of the bright green meadows and gardens, he had taken to illustrating his fellow guests, spreading great joy amongst the vainer personalities. His remarkably lifelike pictures adorned the wall of every bedroom. Adolf had become the most popular person in the building. He seemed to gain some satisfaction from that.

Einstein had given up on his formula to reduce the half-life of plutonium, having wiped his backside on his journal some days ago and thrown it at Dr Stacker. They had continued to deny him plutonium and thus had stifled his genius. That genius had now become sullen and petulant, doing everything he could not to cooperate with the orderlies and doctors.

Lester once again wondered if what they were doing was right, then reminded himself that, no, of course it wasn’t. They were playing God, like all true scientists strived to. It was in their nature to push the limits of responsibility in order to gain greater gifts for tomorrow’s generations. Einstein’s genius indeed demonstrated that IQ was genetically assured and that it was possible to bring back humanity’s greatest minds for worldwide benefit. One day, couples may be able to elect to give birth to a genius or a great artist and release him into the world. What could an Albert Einstein achieve if raised in an environment of learning from birth? He would surely surpass the original.

“Dr Lester? I’m not feeling good.”

Lester glanced up from his notes to see that Norma was standing before him. He was sat in the common room, getting some work done at one of the table, but now had to look up at the image of Marilyn Monroe. Of course, her hair was the natural brown she was born with and not the bleached blonde that the original had favoured. This version of Marilyn Monroe looked anything but glowing and beautiful right now. Her eyes were bloodshot and her lips were dry and cracked.

“Norma? What’s wrong?”

“I…I feel…”

She threw up at once, hot vomit streaming onto the floor in an endless torrent. Her entire body lurched until her legs gave out and she crumpled to the floor.

Lester knees hated him for it, but he dropped down beside Norma and quickly lifted her head. She was choking on her own vomit so he shoved his fingers into her mouth and cleared her airways as best he could. He was horrified when they came back bloody.

“I changed my mind,” she whimpered. “I take it back.”

Lester moaned. “Norma, what have you done?”

By then the other guests had formed a circle around Lester and Norma and all stood in silence, except for Adolf. Adolf broke free of the crowd and joined Lester on the floor where they held Norma between them.

“My sweet, Norma,” Adolf said in a voice thick with worry. “We shall get you help.”

Marilyn Monroe was reincarnated in that moment as blood stained her lips a sumptuous red. Her eyes settled on Adolf and seemed at once happy and sad. “Adolf. My darling, Adolf. If only you had loved me as I love you.”

Adolf swallowed, painfully it seemed. “But I do love you, my dear. It is because I love you that I keep you at bay. I do not wish to love you if I cannot love you completely. You are too good for anything less.”

Norma smiled, blinked slowly. “You’re a good man, Adolf. I’m sorry.”

Adolf wiped at his teary eyes. “Norma!”

Lester shook her. “Norma. Norma, what have you taken?”

“I…drank…”

“She drank this,” said a dull voice in the crowd. Edgar Allan Poe stepped into view, and held in his hand an empty plastic bottle of bleach. Bleach.

Lester stared down at Norma and felt tears fill his eyes. “Oh, you silly girl.”

“I don’t want to live…without…you…” She was looking at Adolf, but her eyes soon turned to lifeless gems and she said no more. Lester eased her down onto the floor while Adolf wept beside her silently.

“It is the worst of times,” muttered Charles Dickens.

Adolf turned his gaze on Lester, a dark shadow. “Help her.”

Lester almost recoiled, but held himself in place. “I cannot.”

“Help her.”

“Adolf, she’s gone.”

“You don’t know that. You can still help her.”

“She would need a hospital and there is no way to get her to one in time. We’re in the middle of nowhere.”

“What is going on?” Stacker demanded as he pushed through the crowd. When he saw Norma lying in a pool of her own bloody vomit, his face fell and the colour drained from his cheeks. “Oh no.”

Adolf sprang up like an athlete and moved in front of the far larger man. “Norma has killed herself and there was nothing anyone could do. How do you help someone who is locked inside a cage? No help for miles. No life. Just this place driving us all insane. Norma may have killed herself, but it is you who gave her no alternative.”

Stacker reached out a hand to Adolf, but Adolf slapped it away. He pushed through the crowd and disappeared.

Stacker looked down at Lester. Lester looked up

at Stacker. “She drank bleach,” he said. “She killed herself.”

Stacker looked mortified. Lester imagined he probably looked the same way. Of all the guests, none had ever been lost for any reason. Ironic, that this Marilyn Monroe had taken her life like the old one had. No, ironic was not the right word. Tragic.

“We need to hold a staff meeting,” Stacker stated.

“And what about us?” Napoleon asked. “Should we all behave as if death is nothing?”

Stacker answered the diminutive general sternly. “You will be addressed shortly. In the meantime, please return to your pods while we take care of Norma.”

For a moment it looked as though the crowd would not disperse, but eventually Napoleon raised an arm and bid them to depart. The mob shuffled its feet and left.

The orderlies arrived and carried Norma away, while Lester was helped to his feet by Stacker.

“She killed herself,” said Stacker. “Perhaps destiny is genetic after all.”

Lester caught a glimpse of Hitler as he left the common room, the man’s face like a thundercloud ready to release deadly lightning.

“If it is,” said Lester. “Then we may be in a lot of trouble.”

-3-

Everyone gathered an hour later around the large conference table in the boardroom, each seated in a comfy, high-backed chair. Lester sipped coffee, hoping to restore his fallen spirits.

“A grim affair,” Stacker stated.

“Was there nothing we could do?” Dr Oliver asked.

Lester bristled at the question. “No. She was already bleeding internally by the time she came to me. How on earth was she able to imbibe an entire bottle of bleach?”

“It was taken from an orderly’s cart,” said Dr Hannigan, a female chemist from Brisbane. “Edgar told me he saw her take it.”

Lester’s eyes widened. “What? Why didn’t he stop her?”

Hannigan shrugged. “He said it is a person’s right to take their life, and by the time he realised what she was doing it would have been too late to stop her anyway.”

Dark Ride

Dark Ride Gripping Thrillers

Gripping Thrillers Hell on Earth Trilogy: The Complete Apocalyptic Saga

Hell on Earth Trilogy: The Complete Apocalyptic Saga Hell on Earth- the Complete Series Box Set

Hell on Earth- the Complete Series Box Set Witch: A Horror Novel (The Cursed Manuscripts)

Witch: A Horror Novel (The Cursed Manuscripts) 12 Steps

12 Steps A is for Antichrist

A is for Antichrist Blood on the Bar

Blood on the Bar Ravage: An Apocalyptic Horror Novel

Ravage: An Apocalyptic Horror Novel Terminal (Major Crimes Unit Book 4)

Terminal (Major Crimes Unit Book 4) Wings of Sorrow (A horror fantasy novel)

Wings of Sorrow (A horror fantasy novel) Blood on the Bar (Lucas the Atoner Book 1)

Blood on the Bar (Lucas the Atoner Book 1) Tar: An apocalyptic horror novella

Tar: An apocalyptic horror novella M is for Matty-Bob (A-Z of Horror Book 13)

M is for Matty-Bob (A-Z of Horror Book 13) Animal Kingdom

Animal Kingdom Animal Kingdom: An Apocalyptic Horror Novel

Animal Kingdom: An Apocalyptic Horror Novel Thrillobytes: bite-sized horror

Thrillobytes: bite-sized horror ASBO: A Thriller Novel

ASBO: A Thriller Novel Legion: An Apocalyptic Horror Novel (Hell on Earth Book 2)

Legion: An Apocalyptic Horror Novel (Hell on Earth Book 2) J is for Jaws (A-Z of Horror Book 10)

J is for Jaws (A-Z of Horror Book 10) E is for Exterminator (A-Z of Horror Book 5)

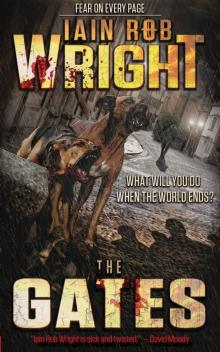

E is for Exterminator (A-Z of Horror Book 5) The Gates: An Apocalyptic Novel

The Gates: An Apocalyptic Novel L is for Lamia (A-Z of Horror Book 12)

L is for Lamia (A-Z of Horror Book 12) B is for Bogeywoman (A-Z of Horror Book 2)

B is for Bogeywoman (A-Z of Horror Book 2) G is for Genome (A-Z of Horror Book 7)

G is for Genome (A-Z of Horror Book 7) The BIG Horror Pack 2

The BIG Horror Pack 2 The Final Winter: An Apocalyptic Horror Novel

The Final Winter: An Apocalyptic Horror Novel The World's Last Breaths: Final Winter, Animal Kingdom, and The Peeling

The World's Last Breaths: Final Winter, Animal Kingdom, and The Peeling C is for Clown (A-Z of Horror Book 3)

C is for Clown (A-Z of Horror Book 3) Hot Zone (Major Crimes Unit Book 2)

Hot Zone (Major Crimes Unit Book 2) The Yacht (Year of the Zombie Book 3)

The Yacht (Year of the Zombie Book 3) Slasher: the Escape of Richard Heinz

Slasher: the Escape of Richard Heinz I is for Ice (A-Z of Horror Book 9)

I is for Ice (A-Z of Horror Book 9) Year of the Zombie (Book 3): The Yacht

Year of the Zombie (Book 3): The Yacht The BIG Horror Pack 1

The BIG Horror Pack 1 Extinction: An Apocalyptic Horror Novel (Hell on Earth Book 3)

Extinction: An Apocalyptic Horror Novel (Hell on Earth Book 3) Sea Sick: A Horror Novel

Sea Sick: A Horror Novel The Peeling Trilogy

The Peeling Trilogy The Housemates: A Novel of Extreme Terror

The Housemates: A Novel of Extreme Terror Sam

Sam